He started sincere, but finally gave in to old party methods

By Swapan Dasgupta

My initiation into the rarefied political salons of Delhi took place on the evening of December 31, 1984. I was on a fortnight’s visit to India to study the general election that had been called after Indira Gandhi’s assassination. As I was at a loose end that evening, an old college friend who was well connected to the city’s liberal fraternity suggested I accompany her to Romesh and Raj Thapar’s open house at Chanakyapuri.

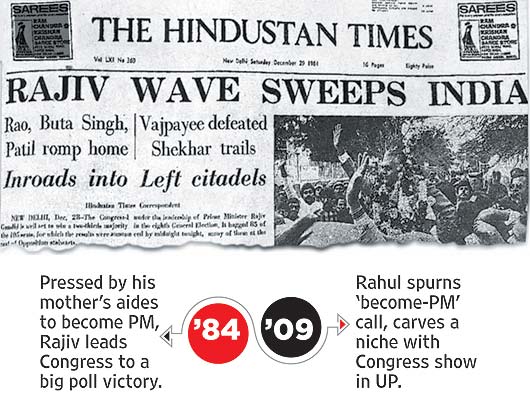

I was in a cocky mood that evening, having won numerous bets over the outcome of the election. In hindsight this may appear surprising, but a perusal of the English-language newspapers of December 1984 will show that the chattering classes expected the Rajiv Gandhi-led Congress to just about squeak through.

Having spent 10 days in Calcutta, I had a very different perspective. Even in strong Communist bastions, it seemed that the new prime minister had captured the popular imagination. There was a wave of revulsion in the middle classes when the imperious CPI(M) leader Somnath Chatterjee brushed away Mamata Banerjee—an unknown Congress candidate contesting the no-hope Jadavpur seat—as she tried to touch his feet after the filing of nominations. The Bengali mashima class (the proverbial neighbourhood aunties) in particular were completely bowled over by the stoic dignity of Rajiv Gandhi as he observed the funeral pyre of his mother—an image repeatedly telecast by Doordarshan, the only TV channel available then. I saw Rajiv speak at an election rally in south Calcutta and observed the awe, curiosity and enthusiasm that greeted him—despite his halting Hindi and lines such as “Akali Dal ka prevarication”. Indira’s funeral pyre was a permanent backdrop, but there is no doubt that in 1984, Rajiv added a substantial incremental vote to the Congress kitty.

If the mood was so sympathetic to Rajiv and Congress in the refugee colonies of Calcutta and the rust belt of Howrah, my assumption was that it would be decisively more so in the states where the Congress was entrenched. When Karan Thapar (he was doing an election programme for a British channel) rang me three days before polling, I told him it wasn’t going to be a mere landslide but an avalanche.

As the results started trickling in, I made a small detour to Connaught Place. Outside the red-bricked offices of the Statesman, a crowd stared at the election scoreboards and announcements. At each announcement of a Congress victory, there were cheers. But an exceptionally loud roar greeted the announcement that Amitabh Bachchan was comfortably ahead of H.N. Bahuguna in Allahabad; and an equally boisterous cheer followed the “flash” that Atal Behari Vajpayee had lost to Madhavrao Scindia in Gwalior.

The party that evening was more akin to a wake. The liberal intelligentsia was not amused by the outcome. There was considerable tut-tutting over the provocatively aggressive advertisement campaign run by the Congress, despair over the quite explicit anti-Sikh propaganda in the localities and occasional mirth over Rajiv’s relative inexperience. An elderly professor mocked Rajiv’s closest aides, the two Aruns: “One sold boot polish and one sold paint. Now they are going to run India!”

To someone born into a business ambience, the corporate backgrounds of Arun Nehru and Arun Singh didn’t seem a liability. Indeed, it signalled a refreshing change from the hypocritical dhotiwallas who dominated the legislatures and the brash kurta-pyjama acolytes of Sanjay Gandhi who were said to have organised the Sikh killings. India, I argued, needed reassurance after the trauma surrounding Mrs G’s assassination; with his awesome majority, Rajiv had the opportunity of bringing in some change.

That evening, as 1984 was rung out, I was in a hopeless minority. Delhi’s genteel liberals had decided that the masses had betrayed the classes and would pay a heavy price for letting emotions get the better of common sense. The liberal intelligentsia that had initially been the cheerleaders of Indira in her fight against the Syndicate in 1969, had been horrified by the Emergency and the rise of Sanjay Gandhi, had torn their hair in exasperation as the Janata experiment proved disastrous, had decided that Rajiv’s election meant giving legitimacy to dynastic succession.

In hindsight, their scepticism was prophetic. Yet, in 1984, only perfunctory attention was paid to this subversion of democratic principles. Actually, the subversion had begun in 1966, when Indira Gandhi took over from Lal Bahadur Shastri. But Indira’s accession was not regarded as dynastic politics for two reasons. First, her appointment was endorsed by Congress MPs after an election that also involved Morarji Desai. Secondly, Indira was perceived by the “progressive” wing of the Congress as a foil to the party bosses. She had a claim independent of her status as Nehru’s daughter.

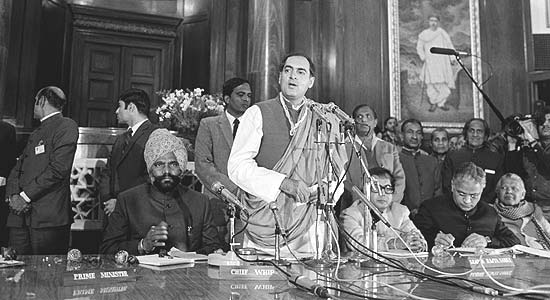

It was the Emergency and the rise of Sanjay Gandhi that signalled the end of innocence. By the time Indira returned triumphantly to power in 1980, it was clear the Congress had been restructured on the basis of loyalty to the leader and her family. When a reluctant Rajiv was made general secretary of the party in 1983, ostensibly to “help Mummy”, the writing was clearly on the wall. When he was sworn in post-haste as prime minister by an ever-obliging President Zail Singh on October 31, 1984, India was mentally conditioned to dynastic succession, at least in the Congress.

Yet, Rajiv’s appointment and election victory was more than just a “The Queen is dead, Long live the King” proclamation. The son was very different from his mother who, in the months before Operation Bluestar, seemed headed for a possible election defeat. In 1984, Rajiv represented a freshness of style, a partiality to technology (as symbolised by his penchant for computers) and a willingness to break away from his mother’s cussed partisanship.

The term Generation X hadn’t been invented but Rajiv did symbolise the arrival of the “Beatles generation” (Arun Singh’s memorable phrase) at the doors of governance. “We are in power now,” a Cambridge-educated professor at iim told me shortly after the election. He was reflecting the optimism and hope of the well-heeled generation that had chosen to stay back in India through the gloomy years of the shortage economy. The belief that Rajiv would inject decency into politics contributed immeasurably to making dynastic succession acceptable to non-feudal India. He was, after all, the only prime minister since Independence who had earned a living outside politics.

Yet, there was a catch: what one section perceived as decency was seen by the entrenched political class as the arrogance of the English-speaking elite. For a long time, Rajiv never came to terms with the existing rules of the political game; like many before him, he felt he could connect with “real India”, minus the disreputable intermediaries. His “power brokers” speech at the Congress centenary in Bombay in 1985 reflected that restlessness.

Tragically, the unease was short-lived. The headiness of 1984 was in three years replaced by the shoddiness of the Shah Bano U-turn, the Bofors scandal, the departure of the two Aruns and the revolt of the Raja of Manda. By then, Rajiv had been well and truly coopted by the system. The flicker of hope some of us felt that winter evening of 1984 had been extinguished.

No comments:

Post a Comment